ADSL In Jordan

2011-08-03

I’ve heard various complaints from a few friends of mine about the status of Internet connectivity in Jordan, especially ADSL. So I’m writing this article to explain what is going on and why ADSL the way it is, but first, some history.

Back in pre-broadband times, people used dial-up modems to connect to the Internet. The name “modem” came from the fact that data was being modulated (Turned from digital to analog form) to be sent over the phone lines, and demodulated (Turned from analog to digital form) at the other end. This utilized the same frequencies used for regular phone conversations, this is why you could hear the weird sounds if you picked the phone up while being connected to the Internet. Given the relatively narrow frequency range used by phones this technology was limited to about 56Kbps, the best speed I got was back in 2003 which was about 5KB/s for my downloads, and that was considered fast at the time.

Then someone figured out they could fit a much bigger frequency range in existing phone lines. The ingenious thing about this idea was the ability to leverage existing infrastructure and allow phone companies and ISPs (Internet Service Providers) to sell much faster speeds with insignificant investments compared to having to switch the entire infrastructure to fiber optics, also allowing people to use the phone even while being on line.

ADSL stands for “Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line”, which means the technology allowing digital transmission of data over the existing wires of the local telephone network. The “Asymmetric” part means the upload and the download streams are not of the same speed. Home users almost always care more about download speeds, so it only made sense that the technology utilized more frequencies for download. This meant we could now get download speeds of up to 2Mbps, depending on how far you are away from the exchange.

Now for some technical details. Back in the 70s landlines were the only means of telecommunication. Governments laid down huge telephone networks. This is how a telephone network typically looks like. Please note that this is a very simplified diagram.

ADSL is a “Last Mile” solution, meaning it only cares about connecting subscribers to the exchange, and not how the whole network operates, so this diagram is enough for our needs. The interconnections between the exchanges have no effect on ADSL so we’re leaving them out.

As you can see in the diagram, telephone companies run cable bundles from each exchange to street cabinets, then from those cabinets to each house or office. This method is used to organize how the cables are laid down. Each cable bundle can reach up to 5Km in length. Cable bundles (1,200 cable pairs) and cabinets look something like this

As with every electrical signal traveling through a conductor, ADSL signals suffer from 2 electrical phenomena; Attenuation and crosstalk.

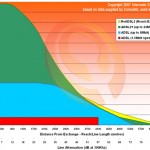

Attenuation is the gradual loss of signal intensity as it passes through a medium. Of course, the longer the distance the greater the attenuation. The greater the attenuation, the slower the final connection speed can be. Here is a graph detailing the relationship between cable length, attenuation, and final connection speed. Note that Orange uses both ADSL (Up to 8Mbps) and ADSL2+

Crosstalk is the phenomenon by which a signal traveling in one circuit creates an undesired effect on another circuit. It is usually caused by undesired capacitive, inductive, or conductive coupling of one circuit to another. What this means is when electrical signals pass through copper cables, they create interference for any adjacent cables. As you can see in the following diagram, all the cables around the victim cable are generating crosstalk which is affecting signal quality. Consequently, the more cables the more powerful crosstalk is.

Crosstalk generates noise, and attenuation lowers the original signal strength and makes it closer to that noise. The higher the speed, the more destructive the noise becomes. If a line is too noisy, the ADSL connection will become too slow or even drop.

To solve this issue, modems perform a sync operation with the exchange, they try to connect to the exchange at the maximum speed possible, then lower that speed to achieve an acceptable noise level, they also leave a noise margin to allow for fluctuations in noise throughout the day. This explains why most homes in Jordan cannot get anything faster than 2Mbps, with some of them getting as low as 128Kbps. This also explains why speeds go down during un-metered (A.K.A. free) download hours in some areas.

Times change, technology matures, content become more rich, and more importantly, competitors arrive. With the clear change of the type of content showing on the Internet and with the rise of competing technologies, i.e. WiMAX, Orange had to start upgrading their network. People were no longer content with the speeds provided by the ancient network built by the government during the 80s, and some of them were bound to leave ADSL and switch to WiMAX, especially since WiMAX didn’t have the phone line overhead and users were no longer confined to the locations they bought the subscriptions for.

Given the number and distribution of users in Jordan, delivering fiber optic connections to each house was out of the question. Contractors charge 22-30JDs per meter for excavation, so connecting a house 300m away would cost 6000JDs in digging costs alone, which is highly unfeasible for a 50JD per month return. In countries like South Korea, population is so dense, each tower has at least 100 users, if you consider a 6000JD cost of laying down the cables compared to a 2000$ monthly return on investment (Assuming 20$ per month for each connection), it’s a very easy decision.

Orange chose a cheaper approach and went with Fiber To The Cabinet (FTTC). FTTC allows Orange to connect a single fiber cable to a digital cabinet close to the user premises, usually next to one of the older copper cabinets. This cabinet acts like a small exchange and contains the equipment to which modems connect. They then connect short cables from the new cabinet to the old one, which is connected to the cable reaching the customer premises. So now, the telephone network looks something like this

I showed a single FTTC cabinet in the figure because they are still not as common as their copper counterparts. FTTC cabinets look like this

How is this useful you might ask. Well, fiber optic cables have very little crosstalk, if any, and attenuation is an order of magnitude smaller than copper wires, especially for long distance. This effectively lowers the distance between the exchange and the modem from 5-6Km to only a few hundred meters, 1Km the most. It also reduces crosstalk between copper wires because those branch out from the cabinet and are not bundled together.

This allowed Orange to reach their current speeds of 24Mbps for some areas. Please note that when I say 24Mbps, I mean for those who live within 100m of a fiber cabinet, any further and the speed will drop. I currently live 500m away from the FTTC cabinet and my line speed is 21Mbps, further distances will get even less speeds.

I’m disappointed with the fact that these FTTC cabinets are not more common and densely distributed. Most areas in Jordan are still covered with copper cabinets, giving most users a best case speed of 4Mbps. Given the amount of money Orange makes, they should be upgrading their network much more rapidly. This is one of the reasons why a lot of areas are leaving ADSL in favor to wireless broadband, especially after the launch of Zain’s HSPA+ service.

I hope this erases some of the misconceptions about ADSL, and I do hope Orange executives become more diligent about their upgrades and have a maximum distance of 500m from any FTTC cabinet.

About Me

Dev gone Ops gone DevOps. Any views expressed on this blog are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.